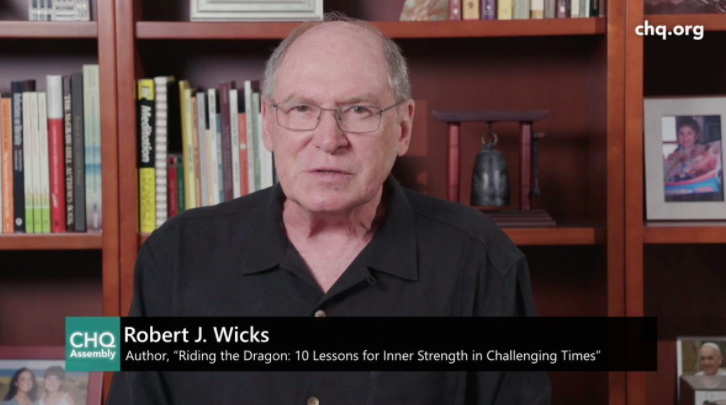

Dr. Robert J. Wicks touches on burnout, resiliency and how to kindle self care

A computer screen separated clinical psychologist Dr. Robert J. Wicks and his audience, but it didn’t phase him. From his Pennsylvania home, he looked at the camera and spoke directly to people experiencing secondary stress and burnout in ministry roles and as physicians, nurses, educators, counselors, psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers and “people like yourselves.”

His second expertise is resiliency psychology and spirituality, “which is designed not simply to help people bounce back from stress, but paradoxically because of it — to become deeper as persons both psychologically and spiritually in ways that would not have been possible had the trauma or stress not occurred in the first place,” Wicks said.

At 2 p.m. EDT Thursday, Aug. 27, Wicks discussed the ways he has guided people as a psychologist and consultant bent toward the spiritual in self-care and resiliency — and how people can put these in practice — in his lecture titled “Night Call: Embracing Compassion and Hope in a Troubled World.”

His lecture marked the end of the 2020 season’s Interfaith Lecture Series, and the Week Nine theme of “The Future We Want, The World We Need.” Wicks is also a recipient of the Holy Cross Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice, the highest honor from the Pope for service to the Catholic Church. In his lecture, Wicks discussed topics from his most recent book Night Call: Embracing Compassion and Hope in a Troubled World. It touches on secondary stress and burnout in roles of both physical and emotional service to others and how a person can deepen their inner life.

He recited a quote from Nobel Peace Prize winner Albert Schweitzer: “I don’t know what your destiny will be, but one thing I know: The only ones among you who will be really happy are those who will have sought and found how to serve.”

But those who serve others also need to take care of themselves in the process.

“Not being aware of the serious stress in our life as we reach out to others — which is a call of every religious faith group — can be quite dangerous,” Wicks said.

Wicks expanded his lecture at Chautauqua to talk about burnout.

“The seeds of compassion and the seeds of burnout are the same seeds,” Wicks said. “Everyone who cares needs to be concerned, not just professional helpers and healers. It’s my belief that for every spiritually committed, compassionate person experiencing significant stress, there’s at least a dozen of us experiencing at least some form of spiritual and psychological burnout.”

Wicks observes guilt when working with nurses and physicians because they can’t save everyone, and in the case of COVID-19, hospitals often don’t have enough equipment to accommodate the high volume of patients. Health care workers also worried about infecting their family.

“Most often, stress is a development rather than a cataclysmic event,” Wicks said.

After giving a talk in South Africa about his book Perspective, a woman approached him and said she couldn’t keep going as a social worker who specializes in helping women who have been sexually and physically abused. The women, who were often poor single moms, had to take off work to go to court. Then the often-male judge would look at the documents and cancel the court date, and would say to make another appointment. The social worker saw herself as a failure.

But Wicks said that she was there for these women when no one else was.

“Don’t you realize we are not in the success business?” he said to her. “We are in the faith business.”

He said that failure increases with proximity to the problem and possible solutions.

“The more we’re involved, statistically the more we’re going to fail,” Wicks said.

When Wicks worked with surgical residents, he started with telling them that they will end up killing people in their career.

“Maybe not through malpractice, but certainly through mispractice, because it is impossible to be at an A-level 100% of the time,” Wicks said. “But commitment is expected of us.”

Wicks described Rabbi Tarfon as a contemporary of Jesus, and quoted him as saying: “The day is short, the work is great, the labors are sluggish and the wages aren’t high and the master of the house is insistent. It is not our duty to finish the work, but you are not free to neglect it.”

In terms of addressing wounds with God, Wicks said it was important to attribute them correctly.

“Are these wounds based on reality, or are they based on our lack of faith and our big ego?” Wicks said.

Wicks described how stress can cause a parallel process, where people mimic the patterns of those they guide, minister to or care for. But Wicks cited a spiritual master who once told him to seek to improve his part in a situation, before trying to “carpet the world,” by wearing slippers to cover his feet.

Life is not acute, it’s chronic,” Wicks said. “A lot of people think, ‘Oh, you have a problem, you conquer it and —’ no, no, life is chronic and comes and goes, but suffering need not be the last word.”

Wicks said people should be present with others, the self and something greater than either of those. Helping others can be as simple as comforting them in a time of need.

And be conscious of how people feel when they’re with you. While watching Desmond Tutu walk onstage, Wicks heard a man say, “Desmond Tutu is a holy man.” When his friend asked him why he thought this, the man said, “Because he makes me feel like a holy man.”

Wicks said that gratitude for others and the little things is important, and to connect with a cause greater than oneself.

On self-care, Wicks referred to humorist Irma Bombeck, who once said, “I think any man who watches three football games in a row should be declared legally dead.”

“We just eat, metaphorically, spiritually, whatever comes along — rather than taking out the time,” he said. “ … We have time for what we want.”

Stephen Covey recommends not only to schedule time, but also priorities. Wicks said people need to make time to be present through meditation, alone time, praying and reading scripture.

But when practicing self-reflection and meditation, Wicks said to avoid arrogance and projecting issues onto others, self-condemnation and discouragement — the last of which is “the last castle of the ego, because you want things to change immediately.”

Self-care is not a process that starts and ends. It’s continuous management.

“Life is not acute, it’s chronic,” Wicks said. “A lot of people think, ‘Oh, you have a problem, you conquer it and —’ no, no, life is chronic and comes and goes, but suffering need not be the last word.”

This is Chloe Murdock’s first season reporting for The Chautauquan Daily. She hopes to visit Chautauqua in the future, but in the meantime she covers news on Chautauqua’s Interfaith Lecture Series. Chloe is a rising senior at Miami University studying journalism and international studies. When she isn’t leading The Miami Student magazine or writing for The Miami Student newspaper, Chloe enjoys practicing martial arts.