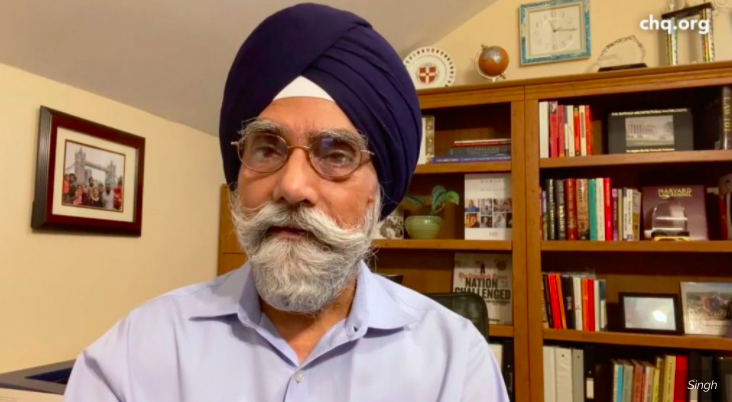

Satpal Singh explores Sikhism creation and how to honor humans’ shared divine light on last Interfaith Friday

Satpal Singh gave the last Interfaith Friday lecture of the 2020 season on his perspective of creation and humanity as a Sikh at 2 p.m. EDT Friday, Aug. 28, on the CHQ Assembly Video Platform. Vice President for Religion and Senior Pastor Gene Robinson said that Singh’s words demonstrated a theme in the Interfaith Friday series.

“One of the reasons that I do this Interfaith Friday program is for people to see how much we have in common with one another, although we would use different words and different practices to express our own own spirituality, our beliefs in the divine and so on,” Robinson said. “… In this multitude of religions, we have this one theme that keeps coming through. Despite the fact that we’re each holding a different piece of the divine, … none of us can comprehend all of it. And what you’re saying has really demonstrated that.”

After the lecture on the CHQ Assembly Video Platform, Robinson joined Singh in a subsequent Q-and-A fueled by questions from Robinson and the audience, who could submit questions through the www.chq.questions.org portal and on Twitter with #CHQ2020.

Singh researches neurodegenerative diseases at the State University of New York at Buffalo. Outside of his career, he is the father of Simran Jeet Singh, who has also spoken at Chautauqua on Sikhism, and Satpal himself is a thought leader on Sikhism in interfaith dialogues and on social justice issues.

According to the Guru Granth Sahib, the central Sikh scripture, there is one universal god who created everything. But this god is formless, without physical traits or a gender. Singh referred to God as “their” to reflect this. While he said a formless god is also difficult to describe, this formlessness is like the concepts of gravity, space and time — though in Sikhism, God also created those, too.

“In a similar way, we can feel love, which is also formless and can permeate our being,” Singh said.

God existed before creation — no land or sky, only darkness.

“Only the divine existed in a profound trance,” Singh said.

Then the divine created the universe.

“From a non-manifest state, the divine became manifest,” Singh said.

Singh sees elements of the Sikh creation story in the Big Bang Theory, the most accepted scientific theory on how the universe began.

“In both cases, starting with nothing, there was a sudden unimaginable force that created an entire known universe,” Singh said.

The divine created it, and also became part of it. Singh said that humans are not only a creation of the divine, but a manifestation, meaning that humans embody the divine itself. The Guru Granth Sahib compares the divine to the ocean, and each human as a wave in the ocean.

“There is no difference between the water in the ocean and the water in the wave,” Singh said.

In Sikhism, the spiritual pursuit of a life is to realize this and become one with the divine. But this is not on a physical plane. Any physical action, such as going on a pilgrimage, dipping oneself in holy water, fasting, facing in a certain direction, praying in a certain language, eating a certain way, is not related to the spiritual journey — though these actions can help prepare someone for spiritual pursuits on a physical or a societal level.

Since the entire world has been created out of the same divine light,” he said, “how can one person be good and one bad in the name of religion, gender, caste or anything else?”

“Some of these actions may offer us health benefits or other benefits at the level of our physical body or societal principles, but they do not offer us any sort of spiritual advancement,” Singh said. “This may seem odd coming from someone who looks like me. My turban is not a ticket to the realm of the divine. The turban is my identity as a Sikh.”

For Singh, his turban serves as a reminder to himself to maintain Sikh values and ethics, and to make commitments to stand up for equality. Because there is a divine light in every human, Singh said that how a person chooses to follow their spiritual path does not matter.

“If you are a Christian, be a good Christian,” Singh said. “If you are a Jew, be a good Jew. If you are a good Sikh, be a good Sikh.”

He said that recognizing the divine light in every human also means that no person can be greater or lesser than another. He compared it to the idea of water from the same pitcher that fills cups, though the cups all have different colors and shapes.

It’s a matter of practicing complete equality — absolute equality, with everyone sitting together to eat irrespective of religion, caste, gender or social status, or any other divisions among us,” Singh said.

“Since the entire world has been created out of the same divine light,” he said, “how can one person be good and one bad in the name of religion, gender, caste or anything else?”

Thus, the concept of hurting another human who possesses the same divine light becomes illogical. Singh said it was like two brothers with the same mother fighting over whose mother is superior.

“It does not make sense to fight or brutalize others in the name of religion, which we often do,” Singh said.

The concept of this shared divine light, which Singh said was an intrinsic, immeasurable value, is why religious houses of worship, including Sikh gurdwaras, offer free meals to anyone who visits. In Sikhism, this tradition is called langar. With the help of donations and volunteers, the Golden Temple in Amritsar, India, is the largest gurdwara and feeds between 40,000 per day on average and more than 100,000 on holidays. Regular-sized gurdwaras can serve thousands of meals every day. Gurdwaras have offered food during Hurricane Katrina, earthquakes, tsunamis, wildfires, flooding, conflicts in Syria, in refugee camps, and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It’s a matter of practicing complete equality — absolute equality, with everyone sitting together to eat irrespective of religion, caste, gender or social status, or any other divisions among us,” Singh said.

Singh said that healthcare workers, community organizers and volunteers giving their time and energy to help during the COVID-19 pandemic expressed the greatest form of this spirituality.

“This is the divine connection that we all share with one another and our creator,” Singh said.

This is Chloe Murdock’s first season reporting for The Chautauquan Daily. She hopes to visit Chautauqua in the future, but in the meantime she covers news on Chautauqua’s Interfaith Lecture Series. Chloe is a rising senior at Miami University studying journalism and international studies. When she isn’t leading The Miami Student magazine or writing for The Miami Student newspaper, Chloe enjoys practicing martial arts.